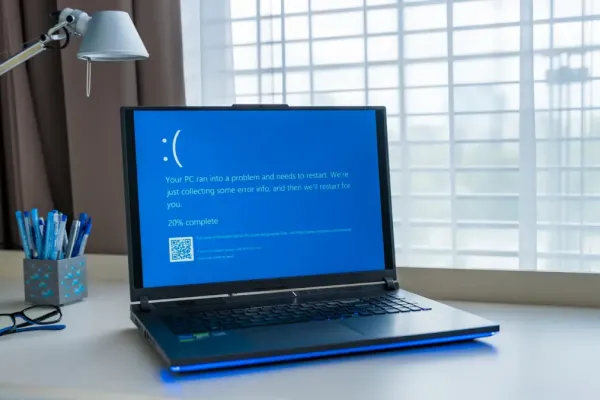

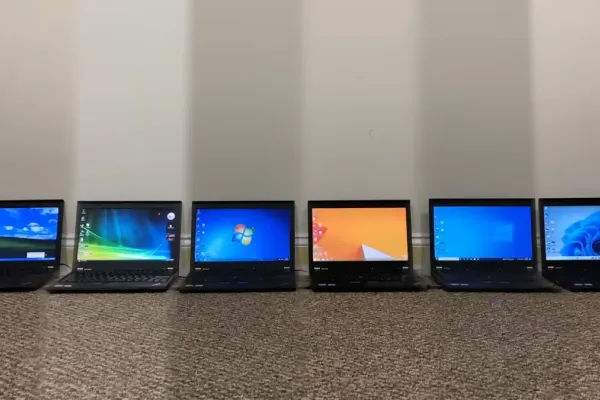

The saga of the FCKGW volume licensing key is a story often told among Windows enthusiasts and industry insiders alike. As Dave Plummer, a key developer of Windows Product Activation (WPA), recently revealed, this notorious key was not a product of hacking wizardry but rather a catastrophic leak with lasting implications for Microsoft's licensing strategy. The FCKGW-RHQQ2-YXRKT-8TG6W-2B7Q8 key became the subject of legend due to its widespread use in circumventing activation requirements during the early days of Windows XP.

Plummer, instrumental in designing the hardware ID and product key verification processes for WPA, uncovered the truth behind the key on social media platform X. He highlighted that FCKGW was not a fluke or a hacking triumph but was actually a legitimate volume license key that fell into unauthorized hands. This key, whitelisted in Windows XP’s activation checks, allowed a seamless bypass of activation prompts when paired with special volume install media.

The Leak and Its Consequences

The leak itself is traced back to 'Devil's Own,' a notorious warez group who acquired and distributed the VLK along with the special media. This occurred approximately five weeks ahead of Windows XP's public release, setting the stage for mass unauthorized installations. Pirates seized this opportunity to bundle the key with a pre-activated version of XP, famously avoiding activation timers and watermarks.

The release of SP2 and subsequent service packs saw Microsoft adopt more stringent measures. The FCKGW key's blacklisting and the eventual removal of volume license keys tightened controls to enhance stability and resolve support issues. Beyond its immediate impact on distribution, this leak prompted Microsoft to refine its approach to product activation significantly.

Impact on Users and Broadband Challenges

The appeal of circumventing activation persisted, even as broadband technology was not yet widespread. Downloading the 455.1 MB XP release with the FCKGW key on dial-up could take upwards of 24 hours, whereas a modest 512 kbps ADSL connection could cut this time down to a couple of hours. Despite these hurdles, many took the plunge, drawn by the allure of bypassing activation entirely.

Today, Windows XP lives on for retro computing enthusiasts, but the FCKGW key’s usability is confined to older systems or virtual machines. Though the key itself no longer functions due to its blacklisting, its legacy lingers—a reminder of an era when software piracy required clever exploitation and when Microsoft’s strategies were put to the test. For stability and support, later service packs transformed Windows XP from a pirate’s playground to a robust operating system, concluding the saga of FCKGW’s unlikely journey.